By Myra Colis

Kabaelan kadi ti igorot ti makatorpos iti adalna? (Can an Igorot complete an education?) This is just one of the many examples of very offensive sentences that are seemingly now prevalent in many school textbooks/modules in the Philippines. Thanks to the COVID-19 lockdown and quarantine measures, parents and guardians can now have a closer look on what’s being taught at schools, especially in the context of culture and identity. Naturally, many fellow indigenous people are angered and offended by these misrepresentations. Some blame the Department of Education in both national and regional levels in the Philippines for not taking enough responsibility to at least fact check what goes in school textbooks and other learning materials. And some others believe this is another example of mainstream prejudice or discrimination against the Igorot Cordillerans. As for me, this is plain ignorance and lack of due diligence on the part of those producing these supposed to be educational materials.

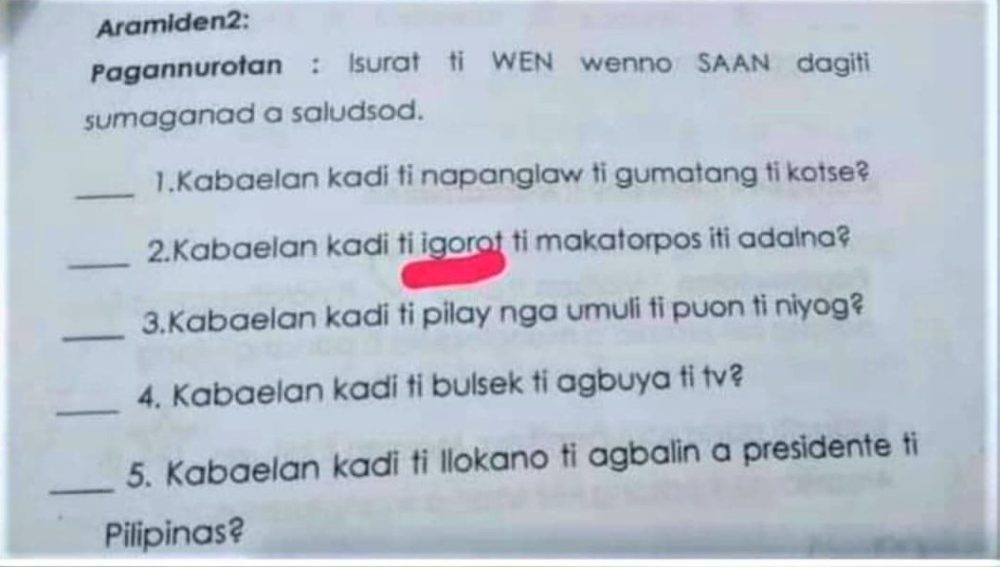

To best illustrate, below are few of the many examples circulated by netizens who are clearly troubled by what has become of the contents and concepts that are taught at Philippine primary schools. Being angry myself for what I see will do me no good, so the least I could do is to respond to each of the examples below with some facts and considerate corrections. To begin with, I took the liberty of translating the examples into English, followed by brief explanations why these examples need to be corrected right away!

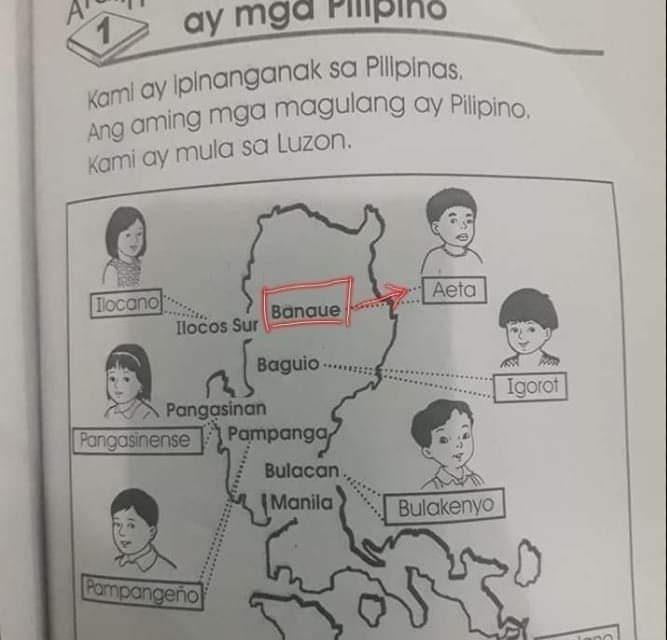

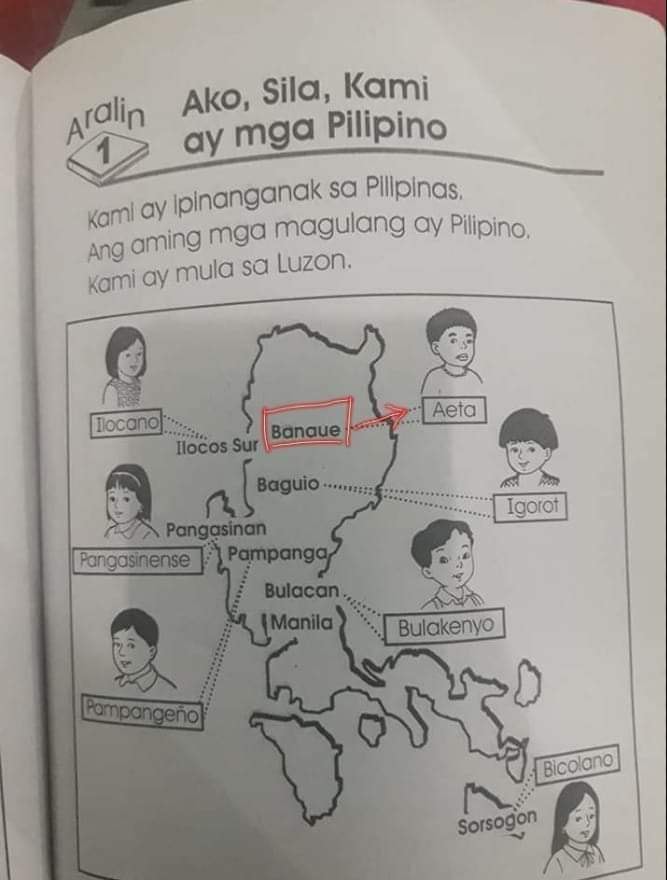

- The marked part of the map indicates that the people in Banaue are called Aeta.

FACT: The indigenous people living in Banaue (a municipality in the province of Ifugao, which is one of the six provinces of the Cordillera Administrative Region or CAR in the Philippines) are called Igorot (and not Aeta). Aeta is the collective term that is used to refer to other indigenous people groups in the Philippines, such as those inhabiting the mountains in Central and Southern Philippines. CAR is situated in the Northern part of the Philippines. It would have been more acceptable if at least the illustration says the people from Banaue are called Ifugao as such is the most preferred term by many of the natives from Ifugao province.

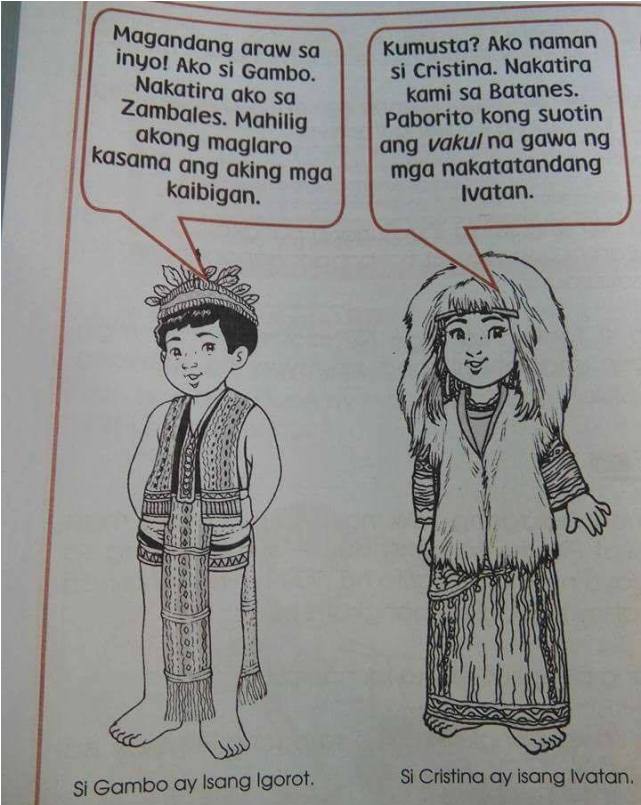

2. The boy says, “Good day to all of you. My name is Gambo. I live in Zambales. I love playing with my friends.” Below caption says, “Gambo is an Igorot”.

Again, another misguided example taught at schools. What’s worse is that these teachings are printed as textbooks, which means these erroneous teachings are documented, preserved and passed on to the next generation as erroneous history not only that of the indigenous people in the Philippines but also about the people of the Philippines in general!

FACT: The indigenous people called the Igorot are natives of the mountainous regions of the Philippine Cordillera, while those who inhabit the mountainous areas in Zambales are called Aeta. There is a huge difference between the two.

3. The underlined words says: “The Ifugao Rice Terraces, which you can find in the region of Ilocos…”

FACT: The Ifugao Rice Terraces is located in Banaue, Ifugao (not in Ilocos). The Ilocos Region is situated in the northwestern coast of the Philippines, far from the rice terraces in Ifugao because Ifugao is a landlocked province that is situated right in the middle of the Cordillera region.

4. The term ‘Igorot’ is defined as the people living in the mountainous region of the provinces of Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, and La Union, as well as the people in the outskirts of Pangasinan. In the CAR (i.e. Cordillera Administrative Region), you can find the Igorots from Italy.

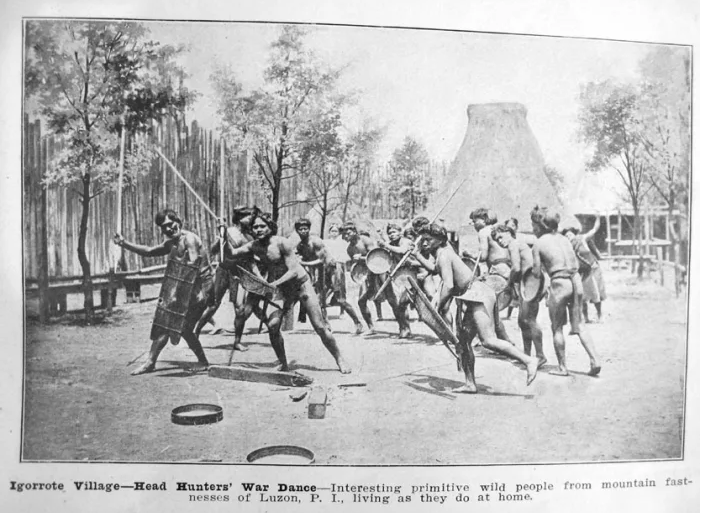

FACT: Apart from the emphasis on places not belonging to the Philippine Cordillera region, what obviously doesn’t make sense in this definition is the association of the Igorot to Italia! Where does that even come from? I know there are many Igorots who are now living in Italy, but it is the case in many other countries across the globe! And by the way, our Igorot ancestors used spears and shields as you can see on the image below (not bows and arrows as illustrated above).

5. The encircled text says: “You saw one of your classmate teasing an Igorot because of his/her looks.”

FACT: The given sentence comes from a common misconception that many non-Igorot Filipinos hold as facts about who the Igorots are and how we Igorots look like— that is, that Aeta and Igorot are one and the same. The truth is that they are entirely two different groups of indigenous people with their distinct beauty, wit and uniqueness. Besides, what’s with the looks of the Igorot that is subject to teasing or bullying? Below is a group photo of us Igorots here in the Netherlands—is there something of our looks that should be teased or bullied?

The point is: there is really no point in pointing out the unique differences of individuals, groups or tribes in a way that implies indifference towards the uniqueness of the native people. Why not just say, “you saw a classmate of yours teasing a boy because of his looks”? I believe this general statement can also achieve the educational objective of the exercise without being mean and discriminatory.

6. The highlighted sentence says, “I’m not going to play with my classmate who is an Igorot because of the way s/he dresses up.”

FACT: Perhaps the exercise is meant to evaluate whether a pupil can determine right from wrong behaviours by answering TAMA (right/true) or MALI (wrong/false). There is definitely nothing wrong with the construction of the sentence, and the most likely expected answer would be MALI. However, the point in this example is again the negative implication of the sentence itself. What is wrong with the way the Igorot dress up? And even if say one comes to school with his or her native attire, what’s wrong with that? Besides, there are many other examples that could be used in this kind of exercise. Why point out on the cultural differences of people in the society and paint them in a negative way? Shouldn’t it be the other way around? So how about using this sentence instead: “I will be playing with my classmate who is an Igorot because s/he is proud of who s/he is”?

7. Answer YES or NO: Can a poor man buy a car? Can an Igorot person complete an education?/ Can an Igorot finish his/her studies? Can a lame person climb a coconut tree? Can a crossed eye person watch TV? Can an Ilocano person become a president of the Philippines?

What troubles me much on this kind of ‘learning’ exercise are as follows:

- What exactly is this exercise for? If these questions are meant to test a pupil’s analytical thinking, then the exercise is terribly asking the wrong questions. Besides, there is no definite answer to the questions posted above because these are subjective or opinionated questions that require subjective or opinionated answers. In short, there could be no right or wrong answer; whether to answer YES or NO depends on the situation.

- In fact, the answers to above statements could all be YES. Why not, right? And who are we to say they can’t?

- If the exercise is meant to simply answer YES or NO, wouldn’t it be better if the sample sentences be facts rather than opinionated statements? For instance, instead of asking “Can an Igorot finish his/her studies?”, wouldn’t it be better if the question goes in the line like “Does it take four years to finish high school in the Philippines, YES or NO?”, “Is ‘Igorot’ a collective term given to the indigenous people from Zambales, YES or NO?”, and so on.

A simple call for action to whom it may concern

To those who are responsible in planning, making and producing all these learning materials for our innocent young learners of today, I for one, with all the many concerned parents, guardians, citizens and netizens out there, would like to think that something has already been done and that such erroneous materials have already been corrected and replaced by now. Needless to say, we are now in the 21st century, surrounded by an avalanche of research studies and reliable information that can easily be accessible over the Internet (see MABIKAs Resource Center for starters!). Our young learners deserve much better than this, and as parents, guardians, educators, school administrators, government leaders, policy makers, and Filipino citizens with a diversified, rich, and beautiful cultural heritage, we can definitely do better than this! By saying NO to ignorance and YES to knowledge, we can all further say YES to understanding and NO to prejudice! And this is what our young learners deserve to inherit from us older generations of today.