By Myra Zymelka-Colis

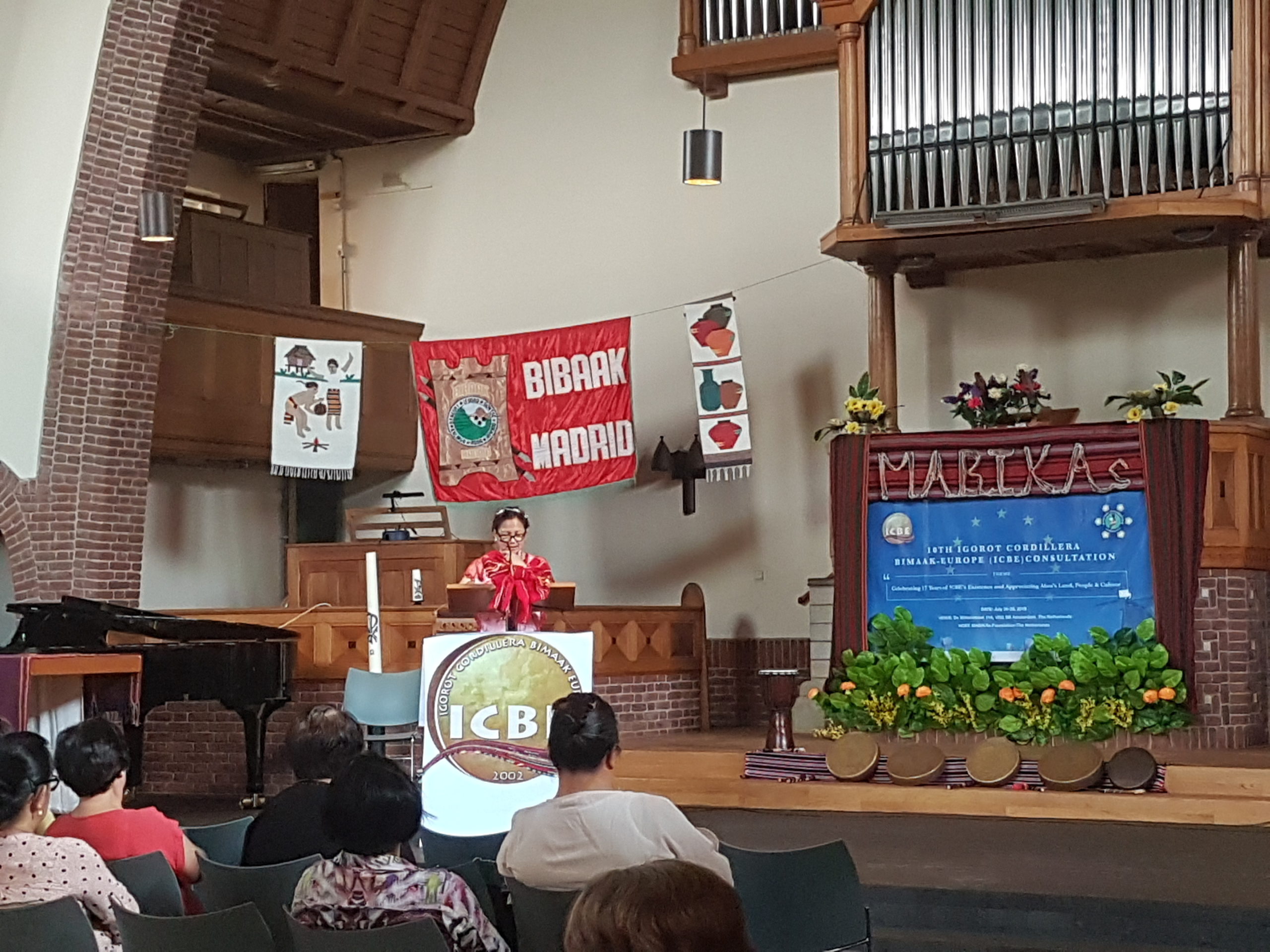

On February 13, 2021, MABIKAs Foundation held its second online monthly meeting under the event banner ‘Tungtungan ti MABIKAs (previously held as ‘Tungtungan ti Umili‘), of which the topic on cañao or kanyaw was first brought to the table when participants were asked, “what of your culture do you want to preserve and why?”.

In general, a cañao or kanyaw is a special feast of the Igorot Cordillerans or the indigenous people from the Cordillera Admistrative Region (CAR) of the Philippines. It is a special feast that entails community gathering not only for social purposes but also for spiritual reasons. Hence, kanyaw is characterized by the presence of three elements: (1) rituals or ceremonies conducted by an elderly Igorot priest, (2) animal offerings, and (3) playing the gongs or other indigenous musical instrument alongside chanting and traditional dancing (depending on the type of occasion). Merriam Webster dictionary may define the term cañao as ‘a pagan religious feast in the mountain regions of the Philippines’ as it does entail ceremonial butchering of animals as an offering to the gods or spirits of our Igorot ancestors, but cañao as it has evolved from then to now has taken different meanings to different generations of Igorot Cordillerans.

During the ‘Tungtungan ti MABIKAs’ this month, it was evident that one of the lingering questions among us new generations of Igorot Cordillerans lies on whether or not the practice of cañao is still relevant today and whether or not it should be preserved as it was. The idea behind the ‘Tungtungan ti Umili’ sessions is to have a platform for community members to share personal cultural experiences during our younger years and share with one another what’s left of those traditional ways, values and learnings that were taught to us by our Igorot forefathers to remember and live by. Hence, below summary of PROs and CONs is a product of first-hand information gathered from the participants who are Igorot Cordillerans themselves and have experienced and gained insights from this traditional Igorot practice called cañao .

WHY TO CAÑAO (PROs)

PRO #1: It’s a traditional practice. As our elder Rev. Cesar Taguba has reminded us during the discussion, the practice of kanyaw is in fact a mechanism of survival for us Igorot Cordillerans; it is all the elements in the practice itself that connect the present generation of Igorot Cordillerans to the past by invoking the spirits of our Igorot ancestors as the ritual begins. It is through this practice that we as indigenous people from the Cordillera region can connect not only with our ancestors but also with nature. In her article entitled, “Rituals as survival and healing mechanism”, author Penelope Domogo also said that it is through the ceremonial practice of kanyaw that the bonds between families and relatives are strengthened and the roles of our Igorot elders are affirmed.

PRO #2: It’s a form of community building. The practice of kanyaw is also all about building relationships, getting connected with family, friends, neighbours and the rest of the community. It is this practice that keep the indigenous people intact. Kanyaw has always been a part of the seasonal cycle of the farming life of the Igorot Cordillerans, especially during the old times when the season of harvest is celebrated with thanksgiving and merry-making in the form of a kanyaw.

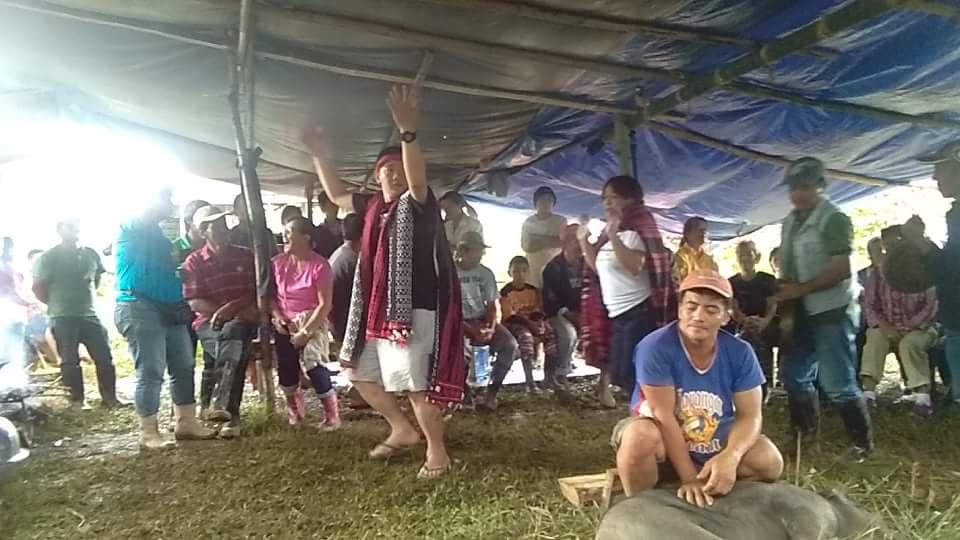

PRO #3: It’s a way of sharing. While many will clearly argue that a person can’t get rich by holding kanyaw every now and then, some others also believe that a person can’t get rich by not sharing at all. The practice of kanyaw is, therefore, traditionally perceived as a way of sharing resources and blessings to the rest of the family clan and to the community. Below photos also illustrate a good example of the ‘sharing’ aspect of kanyaw, whereby people in the community can gather together not only during eating time but most especially also during the preparation period– women will typically offer help in peeling sweet potatoes, making and serving brewed coffee or washing the dishes, while men will do the butchering of the animal, cooking, and serving the meat, as well as beating the gongs to start setting the mood for the feast.

WHY NOT TO CAÑAO (CONs)

CON #1: It’s not economically practical. The Igorot Cordillerans hold kanyaw for many different reasons or for various occasions. For instance, the kanyaw practice and ritual could be used as a healing mechanism for a family member who is seriously ill or a farewell ceremony for a loved one who passed away. It could also be performed for happy occasions such as weddings or thanksgiving following a good harvest. Regardless of what the purpose is of holding a kanyaw, the common denominator is that this practice could extremely be expensive as it requires not only one animal offering but more. The most commonly used animals for offering and meals are chickens, pigs, cows or water buffalos; a piece of each one is already costly, so how much more for two and counting. As Luniza Taoil (a MABIKAs constituent from Abra province) said during the discussion, the animal to be butchered also depends on the kind or purpose of the cañao; in events like wedding or funeral/burials, a number of pigs are butchered, and when someone is sick a native chicken will do. In some occasions, the feasting can last for more than a day, which also translates to more expenses. In a worst-case scenario, some families are forced to borrow money or ‘pawn’ properties (e.g. a piece of land) just so one can properly host a kanyaw with all the required number of animals to be butchered and/or avoid losing face for not being able to comply with traditions. Hence, the practice is nowadays perceived as impractical as it pushes someone down to financial ruin, instead of pushing someone up to financial independence.

CON #2: It hurts relationships. With the modernization and urbanization of societies coupled with the rising number of religious denominations along a dramatic shift in lifestyles as well as values; apparently, indigenous families are not exempted to these changes. As a result, there is a growing gap between the old and young members of families or clans, especially when it comes to sticking to the cultural practices. Also due to the impact and huge influence of Christianity, many Igorot Cordillerans are also slowly adapting to the less restricted way of performing the rituals and abiding by the traditional ways of holding a kanyaw. Hence, this is where the clash between the old and the new comes in; staying true to the old ways is of utmost importance for the elders in the family because to them, non-compliance could result to bad luck or unfortunate events for the family, while the younger members of the family tend to believe otherwise. As a result, tensions grow and conflict arises between family members who no longer believe in the strict practice of kanyaw and those who insist of keeping it as the way it was no matter what.

So what then would be our key takeaway considering the PROs and CONs presented above? On that note, we would like to leave the conclusion to you. TO CAÑAO, OR NOT TO CAÑAO, THAT REMAINS THE QUESTION.

Please feel free to share any thoughts, opinions or insights you may have on this matter.

SPECIAL THANKS to the following MABIKAs constituents who have contributed to this article: Renijune Abaya, Heide Banao, Yvonne Belen, Freda Polquiso, Cesar Taguba, Luniza Taoil. Photos taken by Annie Laurie Banglot and Myra Colis.

Other interesting reading materials on the practice of cañao: