From the name of the bill itself, The Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020, the intention is clear. It is an Act to prevent, prohibit, and penalize terrorism. Taken from that perspective, should we as advocates for the rights of Indigenous Peoples (IPs) support a bill such as this? It is an anti-terrorism bill, so who in their right mind would not want that, right? Nevertheless, one cannot really ensure the integrity of this Anti-Terrorism Bill (ATB) or any enacted law by just looking at the title or even at the choice of words used in the entire bill because all these words are subject to multiple interpretations especially when provisions are vaguely stated. Though legislation in the Philippines is far from the core interests and targets of MABIKAs Foundation, we find it important to raise our voices pertaining to the passing of ATB because this bill, when it becomes a law, has direct consequences to the realization of fundamental human rights, including that of our IP rights. To understand where we stand, the MABIKAs Board and Core Group convened online to discuss what the anti-terrorism bill is, what it means to us, and what our personal convictions are on this matter: do we say YES or NO to the bill? Should we join the #junkterrorbill campaign or not?

Back in the Philippines, it is no secret that there is a strong presence of members of the communist rebels in some villages in the mountainous region of the Cordillera. Accounts that we could rely on are direct experiences of some MABIKAs constituents whose childhood experiences in the villages they grew up with are marked by encounters with communist rebels known as members of the New People’s Army (NPA), a designated foreign terrorist organization. They recalled how most of these encounters with the rebels, who come to their villages on a daily basis taking anything they could find useful (e.g. food, bags of rice, chickens), have instilled fear and uncertainty in the villagers’ lives and livelihood, which is farming. Matters get worse when military forces hunting these rebels find them in the village, resulting not only to clashes with firing guns but also false accusations that the farmers are harboring the rebels or that they’re communist rebels themselves. With these dreadful personal accounts, it is understandable that some MABIKAs constituents find the ATB acceptable. These terrorizing acts of such insurgents and also the government’s counter-terrorism operations have to stop. But is the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 the only answer we have?

As much as we wanted to believe that the intention of the ATB is indeed to ensure national security and public order, our understanding of some terms and provisions of this bill says otherwise. To many of us, we are alarmed by a potential threat hiding behind the following lines under Section 4’s definition of terrorism.

“When the purpose of such act, by its nature and context, is to intimidate the general public or a segment thereof, create an atmosphere or spread a message of fear, to provoke or influence by intimidation the government or any of its international organization, or seriously destabilize or destroy the fundamental political, economic, or social structure of the country, or create a public emergency or seriously undermine public safety, SHALL BE GUILTY OF COMMITTING TERRORISM and shall suffer the PENALTY OF LIFE IMPRISONMENT…”

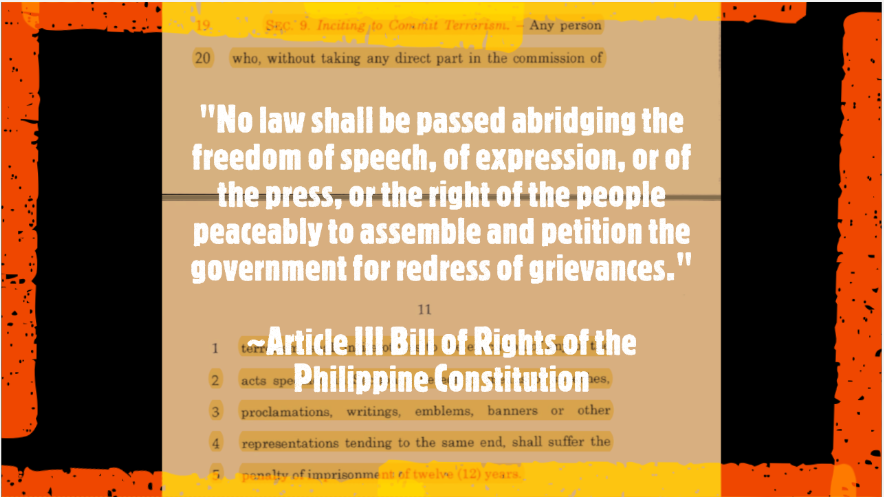

Section 9, further defines who incites to commit terrorism.And that is, “any person who, without taking any direct part in the commission of terrorism, shall incite others to the execution of any of the acts specified in Section 4 hereof by mean of speeches, proclamations, writing, emblems, banners or other representations tending to the same end, shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of twelve (12) years.

Though the bill stated that Section 4’s definition of terrorism ‘does not include advocacy, protest, dissent, stoppage of work, industrial or mass action, and other similar exercises of civil and political rights’, many of us find the above definitions of terrorism contradictory to this exemption. In short, we agree with the one-letter statement put forward by over 100 international lawyers and lawyers’ association when they say, “the bill contains overbroad and vague definitions of terrorism that not only criminalize virtually all acts of freedom of speech, association, assembly, and the press but also criminalize intent justified by baseless, politically motivated accusations.”

Yes, we do understand that freedom of expression is also not absolute. Our right to free speech and expression has its limits, and both international and domestic laws ensure that we respect that. But what concerns us the most is the obvious possibility that this bill can be utilized to further institutionalize national oppression of IP groups, including the Igorots, the Aetas, the Mangyans, the Higaonons, the Lumads, and other IP groups like the Moros, who have already been struggling, fighting for their rights to self-determination and their ancestral lands for all these years. Some of them (if not all) who were brave enough to speak up for their fellow IPs are already red-tagged and branded as terrorists by state forces, leading to vilification, illegal arrest and detention, forced evacuations, massacres, and extrajudicial killings. We are concerned that with the enactment of the ATB, the more that actions such as defending or fighting for our IP rights through speech, protests, campaigns, etc. could be seen as acts of terrorism. For this reason, we appreciate the mass organizations of the student-youth, urban poor, workers, and private individuals who are fearlessly joining the #junkterrorbill campaign, raising slogans like: “Activism is not terrorism.” “Criticism is not terrorism.” “Journalism is not terrorism.” And hence we add,

“Defense of Indigenous People is NOT Terrorism.”

“Empowering Indigenous People is NOT Terrorism.”

“Fighting for IP Rights is NOT Terrorism.”

“Exposing Injustices is NOT Terrorism.”

From this perspective of possible abuse of ATB, we agree with many other concerned civic community leaders, institutions, human rights advocates, business groups, churches, celebrities, journalists, media personalities, athletes, artists, netizens, and even other lawmakers themselves who are taking their stand against the passing of the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020. We congratulate the Cordillera Peoples Alliance (CPA) and more than 62 Baguio-based cultural, student-youth, environmental, development, and human rights organizations, who called for the junking of the Anti-Terrorism Bill. And we thank our Cordillera representatives from Ifugao, Mountain Province, and Kalinga who voted NO to the bill.

We join and agree with the statements put forward by legal organizations like the Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP), the National Union of Peoples Lawyers (NUPL), and the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG). We also appreciate the joint-statement released by Ateneo and De La Salle University on behalf of the 20 university signatories as well as the statement released by the University of the Philippines Diliman (UPD). We agree with their main arguments of the anti-terrorist bill as unconstitutional and vague; it is susceptible to abuse; it curtails civil liberties; it is a threat to human rights; and above all, it is a bid to establish a de facto martial law. To sum up what all these arguments meant for us as indigenous people, Filipino citizens, and human beings; the anti-terrorism bill imperils Philippine democracy.

How then can we work together to ensure that the desired behavior we all wanted is achieved? Is the desired behavior of protecting life, liberty, and property from terrorism only achievable by passing an anti-terrorism bill as vague and unconstitutional such as this? Does everything have to be regulated by sanctioning undesired behaviors in the first place? How about incentive-based regulations to reward desired behaviors? So if the government does want to repeal the Human Security Act of 2007 and change it into the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020, shouldn’t we be all asking ourselves how necessary is this, especially during these times of life-threatening COVID-19 pandemic?

At the moment, the nationwide, multi-sectoral opposition to the ATB has gained international recognition and support from the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. UNOHCHR released a critical report that details widespread human rights violations and persistent impunity in the Philippines. It is encouraging to hear that Amnesty International (AI) and the Human Rights Watch (HRW) also called on the UN to establish an independent investigation body for the extra-judicial killings. And as far as the clashes between NPAs and military forces are concerned, we join with the Roman Catholic bishops, protestant and evangelical church leaders, civil liberties and human rights advocates in their call for the resumption of peace talks between the government and the revolutionary Communist Party of the Philippines-New People’s Army-National Democratic Front of the Philippines (CPP-NPA-NDFP).

In conclusion, MABIKAs Foundation’s plea to those in a position to make a difference is this: please #junkterrorbill. There must be another way, and we are convinced that the anti-terrorism bill is NOT it. This is not about “WE versus YOU”. It is actually more about “WE and YOU”.

(Statement written by Myra Zymelka-Colis & Cesar Taguba on behalf of MABIKAs Foundation-The Netherlands)